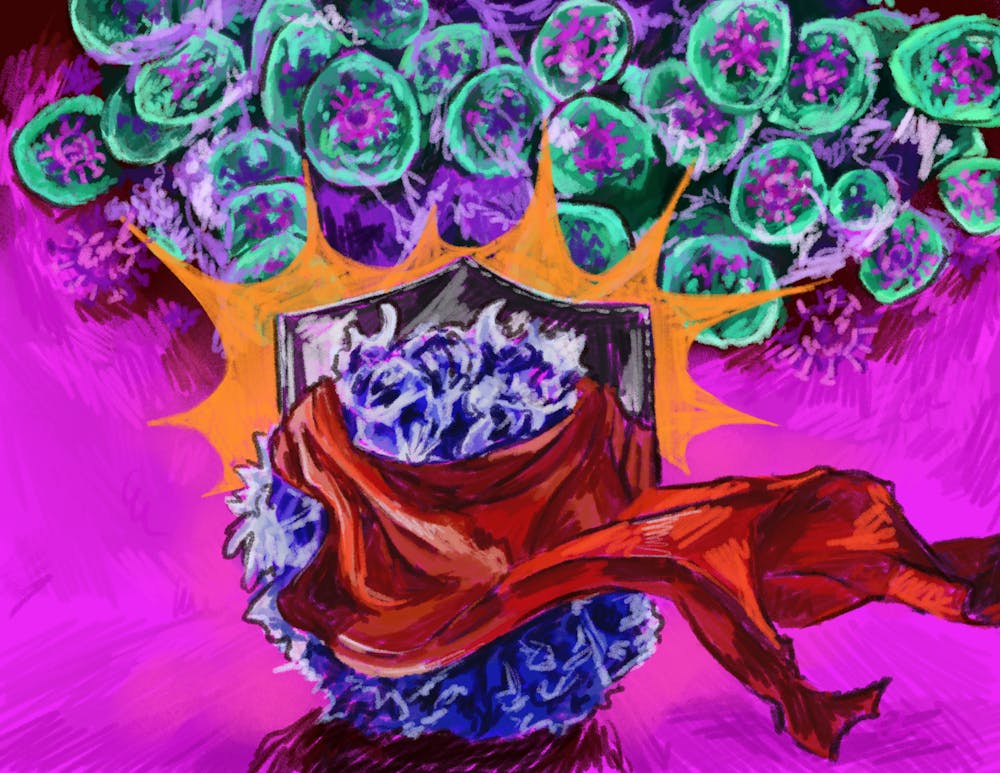

To fight off bacteria and viruses, the human immune system has an army of many different cells — including CD8+ T cells, which are fighter cells in the body. But many pathogens have found ways to evade these cells. The solution, according to some Brown researchers: use nonclassical CD8+ T cells.

Brown researchers discovered that a lesser-known type of nonclassical CD8+ T cell can step in and fight cytomegalovirus, a herpesvirus that latently infects over 80% of the population and is asymptomatic for most. Nonclassical CD8+ T cells get activated by different molecules than normal CD8+ T cells. The researchers’ paper investigated two particular types of these unconventional molecules, called Qa-1 and HLA-E.

“This work reveals how highly resilient our immune system is,” Samantha Borys GS, a contributing author and a member of the Brossay Lab, wrote in an email to The Herald. “Even if one part struggles, another can sometimes take over and protect the body.”

According to the paper, both mouse and human cytomegaloviruses, or CMVs, produce proteins that can be recognized by the nonclassical immune molecules Qa-1 and HLA-E, which then present the antigens to the T cells. These proteins activate specialized CD8+ T cells that the researchers tracked and studied directly, according to Shanelle Reilly PhD ’24, postdoctoral researcher in the Brossay Lab.

The researchers transferred the nonclassical CD8+ T cells into immunodeficient mice and found that the introduction of the specialized cells protected the animals from death after infection with murine CMV.

Reilly explained that the research team selected Qa-1 as a “therapy target” because almost all people possess the molecule in their bodies already. Nonclassical CD8+ T cells can only interact with Qa-1, which only has two copies, or alleles.

This makes it easier to study mechanisms to trigger CD8+ T cells. If there is a “way to trigger the CD8+ T cells” for viral or immune protection, then it holds potential for vaccine development, Reilly said.

CMV is a herpesvirus and causes a “chronic infection,” meaning it has no cure, Reilly added. It also remains a major cause of morbidity and mortality in immunocompromised populations, according to the paper.

Borys added that the virus can be “very dangerous for babies, people with weak immune systems and people who have received organ transplants.”

But according to Borys, the lab identified several antigens that non-classical T cells recognize, “providing valuable insights towards a vaccine candidate that could harness these non-classical T cells to fight CMV.”

The “Brossay lab is (a) pioneer in unconventional T cells” that has created an expanded understanding of cells that are often overlooked, wrote Lalit Beura, assistant professor of molecular, microbiology and immunology.

The lab’s work continues to “shed light” on the attributes of these unconventional T cells, and how they may be useful when the regular T cells fail, added Beura, who was not involved with the study. “They have created a deep knowledgebase on these groups of cells that are often ignored by many scientists.”

“Immune cells wear many hats, are highly influenced by their microenvironment and can exist in a spectrum of states simultaneously,” she wrote. “People tend to see science as black and white, but in the immune system, everything is much more complex.”

Amrita Rajpal is a senior staff writer covering science and research.