As the Office of Admission combs through applications to the class of 2018, staffers are considering a pool with a dramatically different geographic composition than even a decade ago, with a rapid increase in international applicants and a domestic shift out of the Northeast.

The sheer volume of applications has skyrocketed in the last 30 years, increasing from 12,638 for the class of 1988 to 30,423 for the class of 2018, according to data provided by the Admission Office.

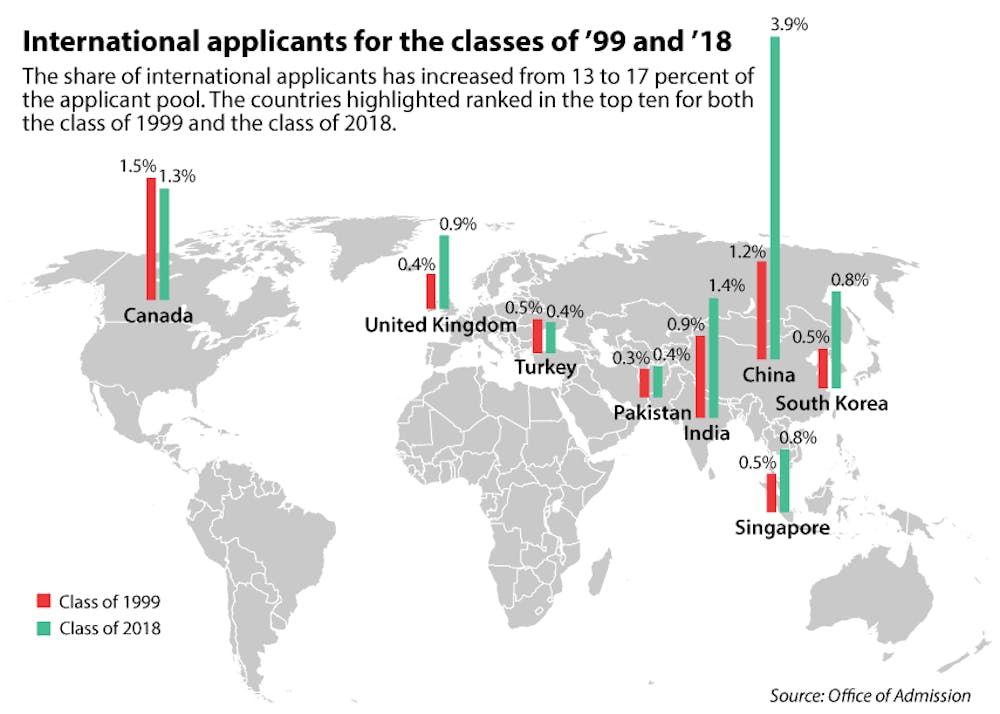

International students made up only 8 percent of applicants to the class of 1988, according to the data. By 1999, these students constituted 13 percent of the pool.

This year saw the highest-ever number of international applicants, as students from foreign countries made up 17 percent of the total pool, The Herald previously reported.

Some countries, like China and India, have especially increased their share of students in the applicant pool.

In 1999, international applicants hailed from 127 different nations, with Canada leading the pack. Canadian applicants made up about 1 percent of the 1999 total pool and 11 percent of those who applied from abroad.

Now, China is home to the most international applicants, representing nearly 23 percent of the international pool — about 4 percent of the total pool.

Students with Chinese citizenship accounted for 2 percent of Brown’s total enrolled student population in 2007, according to data on the Office of Institutional Research website. By 2013, this number had risen to roughly 4 percent. The proportion of Indian students grew from 0.8 percent to 1.4 percent over the same time period.

Getting ‘face time’ abroad

Dean of Admission Jim Miller ’73 attributed the upsurge in foreign applications — and the shift in the top home countries for applicants — to a combination of ramped-up recruiting efforts by the Admission Office in different regions and economic development in certain nations.

To reach foreign students, the University selects specific countries for targeted recruiting. When the Admission Office decides to focus on specific regions, efforts generally continue for “three or four years in a row” to maintain a consistent presence and increase “face time” between students and Brown representatives, Miller said.

The University frequently conducts joint international travel with other universities, an approach also employed domestically. “It’s more effective to reach people when they can see three or four schools simultaneously,” Miller said.

Alums also play a more significant role in international outreach than they do domestically, helping the Admission Office identify different target regions and plan travel overseas. These alums also help reach out to potential students and spread Brown’s brand name, Miller said.

Nicole Alberto, a regular-decision applicant this year from the Philippines, said interacting with a current Brown student who is also Filipino helped her learn about the University, even though she was never able to attend an information session or meet an admission officer.

But the University faces challenges in its push for a globalized applicant pool. Brown lacks the international name recognition of some of its peer institutions, partially due to a comparatively lower graduate student population, Miller said. Many students abroad are more aware of U.S. institutions that have a greater number of professional graduate programs, such as Harvard and Stanford University, he added.

The University’s unique curriculum is foreign to many international applicants. It can be difficult to explain the concept and benefits of the Open Curriculum and a liberal arts education in countries where a narrower academic program in higher education is the norm, Miller said.

Astrid Brakstad, a regular-decision applicant from Norway, said the Open Curriculum is “very different from the Norwegian university system,” which is more structured and does not allow for much academic freedom.

Despite the vast curricular differences, Brown and other American higher-education institutions remain attractive options for foreign students, partially because of lenient student visa policies. The United States “is very liberal in granting student visas” compared to other countries, so many international students choose to apply to U.S. universities, Brakstad said.

In future years, the University plans to continue outreach efforts in East Asia and expand recruitment to countries in sub-Saharan Africa and South America, especially Brazil, Miller said.

Financial options

Many of the countries that have rapidly increased their share of applicants have an “increasingly large middle class that enables people to provide part or all of the costs of tuition,” Miller said.

The University’s need-aware admission policy for foreign students means Brown’s affordability plays a role in international acceptance decisions that it doesn’t domestically.

When considering acceptance decisions, the Admission Office sends a list of possible international students to the Office of Financial Aid to determine how much aid each student would receive under the University’s financial aid policies, said Director of Financial Aid Jim Tilton. The Admission Office may then use this information to make final decisions, he added.

But the University’s policy to meet students’ demonstrated financial need applies to all accepted students, regardless of citizenship status, after the admission process, Tilton said.

While the vast majority of U.S. colleges and universities are need-aware for international applicants, four Ivies — Dartmouth, Harvard, Princeton and Yale — are need-blind for all applicants, according to their respective admission offices. Amherst College and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology are also need-blind for international applicants.

While 46 percent of the class of 2017 receives “need-based scholarship aid,” according to the Office of Financial Aid website, “about 30 percent of the incoming international students receive assistance,” Miller said.

Westward bound?

Domestically, the applicant pool has also shifted dramatically, with an upsurge in applications from the West and Southwest mirroring those regions’ population spikes in recent decades. But the Northeast is still overrepresented in comparison to its share of the U.S. population, The Herald previously reported.

For the class of 1988, students from New York and New England made up about 43 percent of the applicant pool. These states now account for about 24 percent, according to data from the Admission Office.

The West Coast, Alaska and Hawaii showed the most rapid growth in applicants, increasing from 10 percent of the pool for the class of 1988 to 19 percent this year. California in particular powered this spike, as the state accounts for nearly 17 percent of this year’s applicants, Miller said.

Domestic shifts in the applicant pool are the result of broader demographic trends in the nation, Miller said. “Our applicant pool really does reflect where the students are.”

Though many top American high school students are attracted to public universities offering merit-based aid programs, Brown continues to stay in the hunt for such students by offering need-blind admission.

The University’s financial aid policies are aimed at increasing the diversity of the applicant pool, Tilton said. “Need-based aid and being need-blind for domestic students allows any student from any financial background to think about Brown as a realistic option,” he said. Brown’s aid packages are “competitive even with” schools that provide merit-based aid, he added.

Moving forward, Miller said he expects continued shifts in the demographics of the applicant pool. “It’s going to be even more geographically diverse 10 years from now.”

ADVERTISEMENT