In light of the national growth of the #BlackLivesMatter movement, the Washington Post published a database June 30 of every police shooting that has occurred this year. Currently, Rhode Island and Vermont are the only two states with no fatal police shootings.

“I’m really proud we haven’t had the outbursts and the violence that we’ve seen in other communities,” said Mayor Jorge Elorza in a video by Bob Plain, editor of R.I. Future.

“It’s not a coincidence. We’ve spent a lot of time building relationships between the police department and the community,” Elorza said. “We have a lot to be proud of.”

But recent events in the state illuminate contrasting views between police officers and other members of the Providence community.

‘America runs on racism’

A 14-year-old student at Tolman High School in Pawtucket was slammed onto the ground by the school resource officer Oct. 14 because the “suspect” was “walking down the hallway screaming obscenities about what he was going to do to another student,” according to a statement released by the Pawtucket Police Department. In response to the event, which was captured on video, protesters gathered outside City Hall Oct. 15, where police arrested eight juveniles and two adults.

The event came less than two weeks after a Providence Dunkin’ Donuts employee wrote “#blacklivesmatter” on a police officer’s coffee cup Oct. 2.

The Providence Fraternal Order of Police, Lodge No. 3 emailed a statement to Boston.com shortly after the incident condemning the “unacceptable and discouraging” behavior of the Providence franchise employee.

“Our officers, like all other law enforcement agencies, work tirelessly to protect and serve all members of the communities,” the statement reads. “The negativity displayed by the #BlackLivesMatter organization towards police across the nation is creating a hostile environment that is not resolving any problem or issues, but making it worse for our communities.” The statement ends by stating that “ALL LIVES MATTER.”

Dunkin’ Donuts wrote in a statement that the franchise owner of the Providence branch “counseled the employee about her behavior” and apologized to the officer involved.

The fact that the police officer felt offended by the words on his coffee cup is “insulting to America,” said Gary Dantzler, a local Black Lives Matter activist. “There is no compassion … for the black and brown people that have been killed,” he said, adding that the employee made “excellent” use of a “perfect opportunity” to spread the important message that black lives matter.

Protesters gathered Oct. 12 outside a Dunkin’ Donuts shop in Providence, donning signs that read “America runs on racism” and “stop ignoring racism” to support the employee.

Police-on-police violence

Former Providence Police Officer Christopher Owens filed a lawsuit in U.S. District Court Sept. 18 seeking $1 million in damages for being mistakenly identified as a suspect while off-duty.

In September 2012, Owens and his son Tyler — both of whom are black — helped chase down a truck driver, Sean Sparfven — a white man — who was suspected of dealing in stolen vehicles and was the subject of a high-speed chase. When police officers arrived at the scene, they immediately assumed Owens and his son were the criminals and arrested them both.

Owens and his son “were assaulted, arrested, handcuffed and placed in the rear of police cars due to the color of their skin and because they were African Americans,” according to the lawsuit. Christopher Owens is now permanently disabled.

“One officer remarked that all he saw was a big black guy,” the lawsuit states. It also states that the police officers violated the Fourth and Fourteenth Amendments — the right to protection against unlawful search and the right to equal protection of the laws, respectively.

State Police Superintendent Steven O’Donnell acknowledged in a statement that it was Owens who apprehended Sparfven. But O’Donnell told the Providence Journal that Owens “has some responsibility for what transpired in that backyard” because he did not follow the proper procedure for identifying himself as an officer.

A similar situation involving the Providence Police Department occurred in January 2000 when two officers mistakenly shot and killed fellow Providence police officer Cornel Young Jr., who was off-duty at the time.

By the numbers

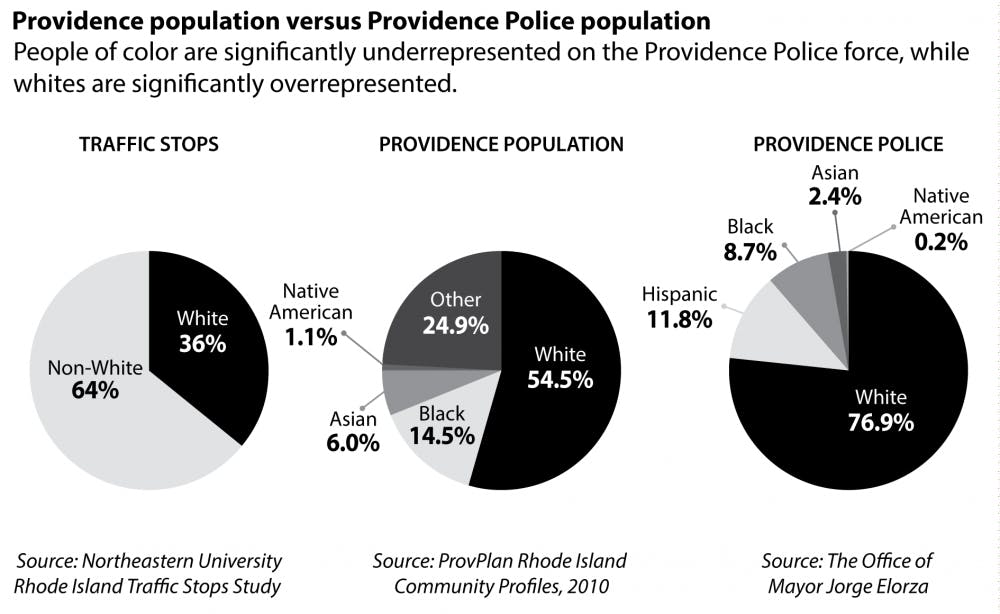

Northeastern University’s Institute on Race and Justice published a report in 2014 showing racial disparities in traffic stops in Rhode Island. Experts reviewed 153,891 traffic stops that 39 Rhode Island police agencies made between Jan. 1, 2013 and Sept. 30, 2013.

The report concluded that Providence Police officers stopped 24.1 percent more non-white drivers than the Driving Population Estimate would have predicted. The DPE — a statistic that accounts for the racial breakdown of the driving population — estimated that 39.9 percent of traffic stops would involve non-white drivers, but in reality, 64 percent involved non-white drivers.

The 2014 report is the third of its kind that researchers at Northeastern have conducted. The same methodology used in 2003 and 2006 produced the same conclusion — non-white drivers are much more likely to be stopped than white drivers.

The racial breakdown of police officers in Providence sheds some light on why various issues of racial profiling and police brutality towards people of color may arise. Minorities are significantly underrepresented in the police force. Of the 424 total officers in Providence, 326 are white, comprising about 77 percent of the total police force. Only 37 — under 9 percent — are black, 50 are Hispanic, 10 are Asian and one is American Indian, according to the Office of the Mayor.

City efforts

Elorza announced in September that the Providence Police Department received a $1.875 million grant from the Community Oriented Policing Services program within the U.S. Department of Justice to hire up to 15 more police officers. The funds will help “strengthen the Police Department, help support community policing, (improve) crime prevention and ultimately enhance public safety,” said U.S. Rep. David Cicilline ’83, D-R.I., in a Sept. 21 press release.

The Police After School Sports program, launched earlier this month, also aims to bridge the gap between the police and the community. A joint effort by Elorza, the Providence Police Department, the Providence After School Alliance, International Game Technology and the Providence School Department, PASS allows off-duty police officers to coach basketball and flag football teams for middle school students across the city.

The program strives to “increase youths’ participation in quality sports programs” and to encourage “young people and officers to build closer relationships with each other,” said Hillary Salmons, executive director of PASA, adding that the sports program, which received $40,000 of funding from IGT, will engage 10 police officers and between 150 and 200 students. The police are excited about building “meaningful relationships with young people in the community,” she said. “They all want to do this.”

State policy

Signed by Gov. Gina Raimondo in July, the Comprehensive Community-Police Relationship Act of 2015 aims to tackle racial disparities at traffic stops. The bill requires all police departments in the state to collect information — age, race, time, reason and whether a search was performed — from all traffic stops over the next four years. The act also bans searches of juveniles unless there is reasonable suspicion. An annual report will be submitted to the Department of Transportation and will be analyzed by Justine Hastings, professor of economics, to identify trends related to racial bias.

The bill is a revision of a previous one that failed to pass because it did not garner enough support in the House of Representatives. This new bill “holds police accountable and provides transparency for the community,” said Steven Paré, Providence commissioner of public safety, adding that one of the challenges of implementing the law will be educating police officers across the state about what is expected of them.

Data will be regularly assessed, and law enforcement administrators will observe the trends on a weekly basis, Paré said. This data will be released to the public periodically, he said, though he did not specify how regularly.

The legislation is “a first step in addressing the racial disparities that we see in policing in Rhode Island,” said Hillary Davis, policy associate at the American Civil Liberties Union of Rhode Island. “There’s significantly more work that will be done afterwards, but we do hope that some of the protections that are included in the law will provide relief to specifically youth and pedestrians who are currently not feeling so safe in Rhode Island.”

It is important to ensure that the data is being collected and constantly evaluated so that “the law doesn’t just exist on paper, but is also used in ways to protect everybody,” Davis said.