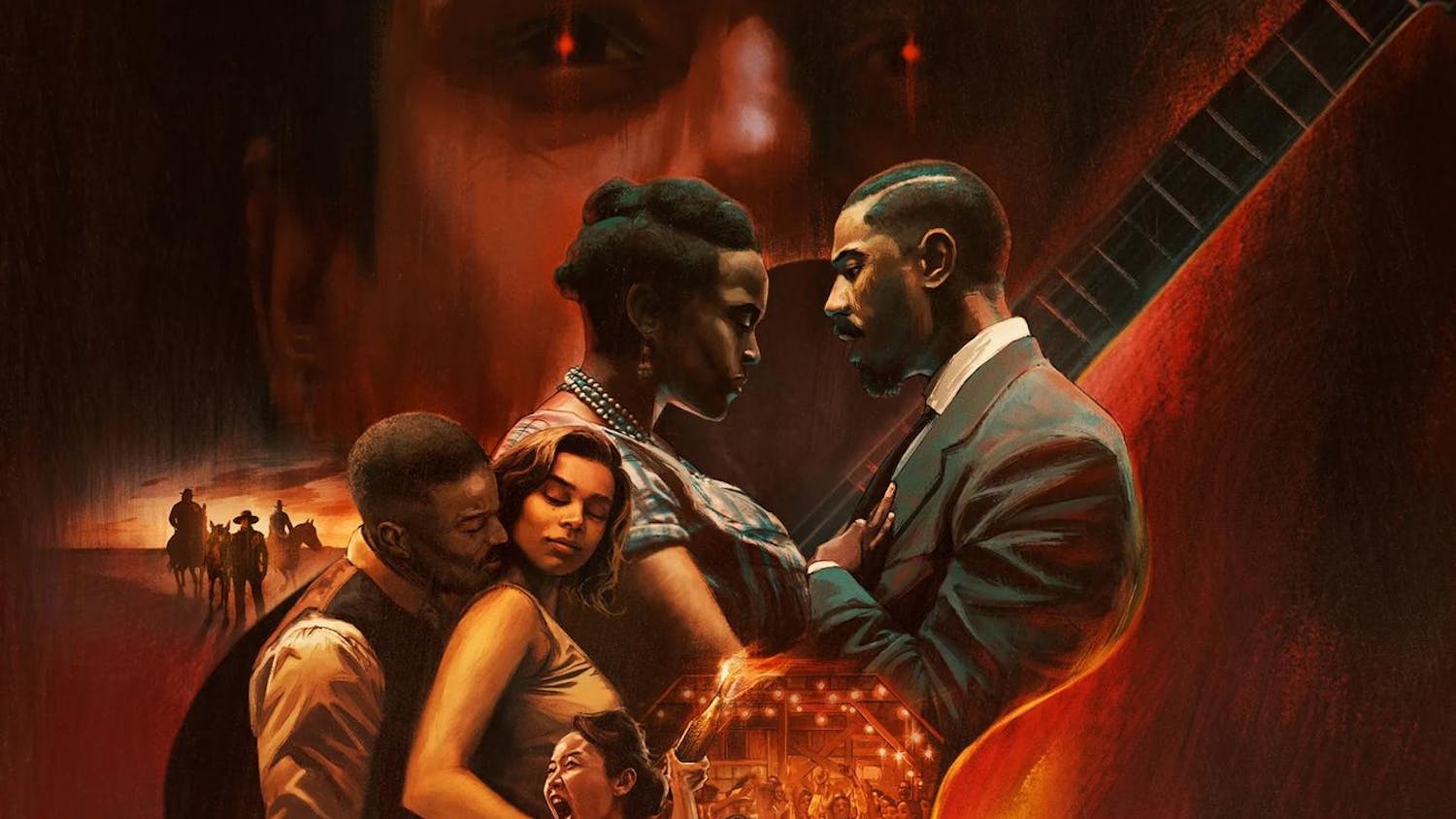

The debacle of Sunday’s Academy Awards best picture award was a fitting conclusion to a category so fraught with tension this Oscars season. Over the past few months, the two-horse race between “La La Land” and “Moonlight” has become so overlaid with political consciousness that a victory for either film would have felt like a validation of one worldview over another rather than a celebration of artistry. It was only natural that the Academy Awards presenters did not even announce the correct best picture winner. The producers of “Moonlight” suffered the indecency of stepping on stage after the producers of “La La Land” accepted an award that rightfully belonged to “Moonlight”. The film’s victory should have represented a tonic — but in place of catharsis, there was only exhaustion.

President Trump was elected Nov. 8, but the trauma experienced by those he marginalized during his campaign lingers. For many, Trump’s election mirrored regression in civil society, an attack on the liberal values that former President Barack Obama had imbued with a sense of permanence during his eight years in office. As a result, those experiencing the anti-Trump sentiment permeating much of our country have begun to interpret random post-election events through the binary prism of political and social progression or regression. This bifurcation reflects a response to political trauma, expressing our desperate urge to understand events across the entire spectrum of civil society as politicized responses. These responses can either represent a corrective to the retrograde nature of Trump’s vision or the mainstream legitimation of his worldview.

Pop culture events have provided a stage on which to reproduce electoral trauma as a therapeutic exercise. In the buildup to the Super Bowl, fans and the media painted the New England Patriots and Atlanta Falcons along a binary. The Patriots, with their extensive personal connections to Trump, played the regressive antagonist, while the Falcons, representing an underdog city with a large black population, were lauded as the tolerant champion of liberals. The actual game played out similarly to the election: Despite nursing a 25-point lead (at which point they had a 99.7 percent win probability), Atlanta lost in overtime to the Patriots.

The best album award at the Grammys experienced similar framing. Beyoncé’s “Lemonade” served as the magnum opus from an artist who has consistently empowered women, especially women of color, throughout her career. Critics celebrated her album’s exploration of grief, rage and reconciliation as a vastly superior creative accomplishment to Adele’s “25,” which was widely accepted as a strong though unexceptional pop album. Adele’s victory released an explosive and painful response on the internet. Again, Trump’s particular brand of white nationalism had supposedly triumphed.

The culmination of these cultural events and the post-electoral traumas they induced only added further weight to the Academy Awards’ best picture race. While “Moonlight” topped most year-end critical charts, “La La Land” enjoyed its status as the massive favorite to win best picture. And while “Moonlight” explored the life of a young, gay black man, “La La Land” reveled in Hollywood pastiche. Undergirding the awards process was a fear that the Oscars’ primarily white voting body — much like that of the Grammys — might not reflect popular opinion, in a manner akin to that of the electoral college.

Popular interest fueled the politically polarized weight of the best picture race, yet neither film showed any interest in making the collective stage a battleground. Indeed, films, albums and even teams that occupy shared cultural spaces rarely reflect the severe dichotomy inherent in the electoral process. Assigning political values to art reflects a response to trauma rather than any legitimate labeling act. Furthermore, particularly in the case of “Moonlight” and “La La Land,” foisting this type of extreme baggage upon two competitors undermines rational discourse that addresses the subtler forms of marginalization that occurred in the awards process.

Perhaps a more productive exercise in moral evaluation can be found not in a political binary but in assessing the casually “benign” forms of racism at play during Sunday’s Academy Awards. There was Justin Timberlake, a white singer performing a hit by Bill Withers, shouting out mid-song to Denzel Washington, “I know you know this, Denzel!” Then, there was Jimmy Kimmel making fun of the name of “Moonlight” star and best supporting actor winner Mahershala Ali. Sunday’s Academy Awards were like the kind of person who recognizes the atrocities of slavery but is blind to the white privilege born out of that history. “Moonlight,” with its black cast and challenge to the toxic historical hypersexualization and dehumanization of black masculinity, has to navigate a cultural sphere that at times proves ignorant to the history of inequity that informs the film’s existence and meaning.

After winning best supporting actress, Viola Davis gave an impassioned call for telling the stories of marginalized voices, saying: “You know, there’s one place that all the people with the greatest potential are gathered. One place, and that’s the graveyard. People ask me all the time, ‘What kind of stories do you want to tell, Viola?’ And I say, exhume those bodies. Exhume those stories.” Moonlight dared to exhume the bodies of buried voices. The privilege of “La La Land” is that it didn’t have to resurrect those buried voices. Award ceremonies and other popular culture events don’t have to split along the extremes of the recent electoral binary to be political.