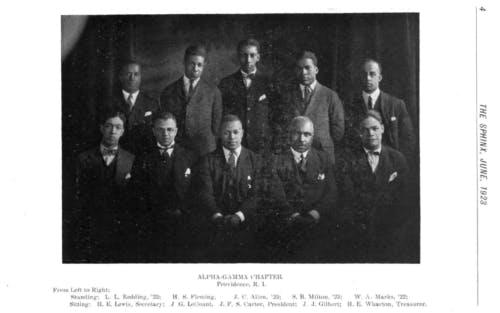

On a Saturday night in February 1923, the brothers of the Alpha Gamma chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha held an initiation ceremony to welcome three new members to their ranks. With the addition of two active members and an honorary member — a renowned Black physician in Providence — the fledgling fraternity began to grow.

The men celebrated with a “jolly evening spent in giving to the pledgees a glimpse of the good fellowship and spirit of Alpha Phi Alpha,” according to brother Joseph Chester Allen, class of 1923, in the April 1923 issue of the national fraternity’s magazine The Sphinx. Celebrations were held two weeks later at Old Fellows Hall in downtown Providence — given that the fraternity had not yet gained official recognition at the University — where the affair had “a delightfully charming atmosphere” and “made the evening a very enjoyable one.”

Founded officially only two years before in 1921, Brown’s first Black fraternity informally began as a debate club. Eight Black students who attended the University in the late 1910s would travel back and forth between Providence and New Haven to compete against Yale.

This year, Alpha Phi Alpha celebrates 100 years of providing a unique space of support and community for Black students at Brown.

‘No home with Brown’: Alpha Phi Alpha is born out of exclusion

“There were a reasonable number of Black students on campus” at the time, Alpha Phi Alpha alum Rodney Robinson ’90 told The Herald. But relatively few Black students attended the University until after World War II, so finding community and support on campus in the face of rampant racism was often difficult.

Not only were there sparse numbers of Black students on campus, they were often excluded from the social life of the rest of the student body. With nineteen active fraternities in 1923, plus three “honorary” fraternities, Greek life was an integral part of campus. Official fraternities alone contained a collective 657 members out of 1,561 total male students at Brown.

“At that time fraternity (and) football were really huge parts of Brown’s culture,” said David Onabanjo ’22, current president of Brown’s chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha. But “Black students were just directly left out of it.”

In 1921, the eight members of the debate club began considering solidifying their club as a fraternity for Black men on campus. They filled out the necessary applications and submitted them to the necessary offices. But the University ultimately turned down the request to form a fraternity, Robinson said. An issue of The Crisis, the official publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, wrote that “college authorities declared there was no room in Brown for a colored fraternity.”

“We did want to be part of Brown, Brown didn't want to be part of us,” Robinson said. “They rejected our application, so therefore we had no home with Brown.”

To maneuver around the University’s decision, the eleven men decided to found a Providence chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha, a fraternity for Black men first founded at Cornell in 1906.

“Our organization was founded out of resistance, out of resilience,” Onabanjo said.

Early chapter events ranged from putting on plays and hosting basketball and football games to hosting “Go-to-High School, Go-to-College” campaigns. Many brothers from this time were honored with awards for their writing and oratory skills as well, including Louis Redding, class of 1923. As Clinton Henry, class of 1925, wrote in The Sphinx, “with our small band of ideal Alpha men, we hope to accomplish great things.”

“They have an excellent spirit, harmonizing and brotherhood among all the members,” said Alpha Phi Alpha national Vice President R.P. Alexander of the chapter in a 1922 issue of Sphinx Magazine.

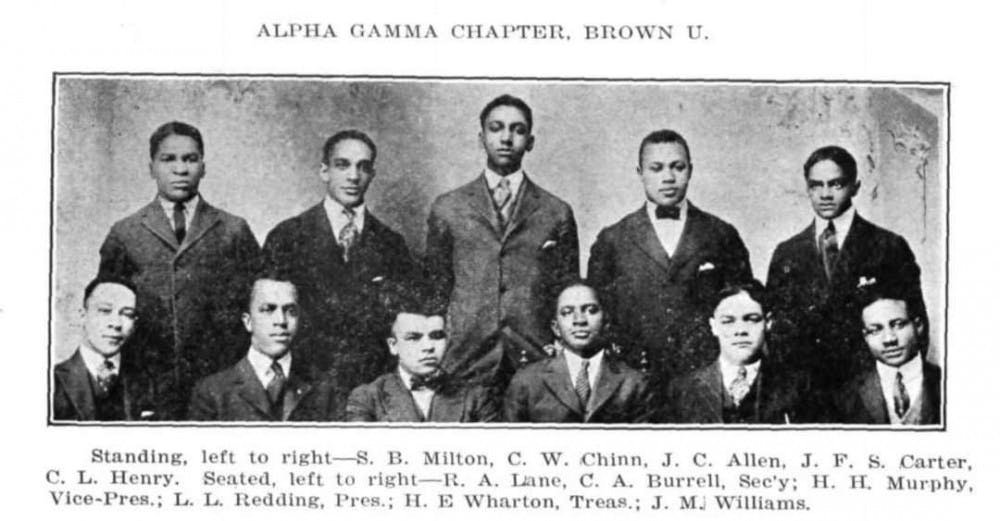

Of the men in the founding chapter, many went on to lead highly successful lives.

Allen went on to attend law school at Boston University, and later opened a law firm in South Bend, Indiana. He was the first Black man on both the South Bend School Board and City Council, and he served as a state representative in Indiana for two terms.

Joseph Carter, class of 1924, was a star football and track athlete while at Brown who “slows down once in a while to go to the theatre,” according to the 1924 Liber Brunensis. Chester Chinn, class of 1920, spent “most of his time in the Physics Lab doping out Kepler's Laws or down at Arnold cutting up cats and fishes,” according to 1920 Liber Brunesis. These two men, alongside Samuel Milton, class of 1924, and Heber Wharton, class of 1924, went on to become doctors.

Henry served as Senior Housing Manager of the New York Housing Authority, while Russell Lane, class of 1921, became an educator and eventually superintendent in Indianapolis.

Jay Williams, class of 1921, was a skilled football player while at Brown, referred to in Liber Brunensis as a “dusky warrior who is as fast on the cinders as he is on the gridiron.” He went on to play professional football for the NFL, work as a football coach at Morehouse College and found Ebony Records in Chicago — where he discovered successful blues singers such as Ma Rainey.

“These gentlemen did this in (the) 1920s, with no Third World Center, no Black deans, no support, no recognition,” Robinson said. ‘They just knew they had to excel and be the best at what they did, and that's what they did.”

Alpha Phi Alpha continues to flourish, resist in the 1980s

Alpha Phi Alpha was no longer active on campus by World War II, though there was always at least one active member living in Providence and maintaining the active status of the fraternity’s charter. The fraternity established its presence on Brown’s campus in 1974, Robinson said, but this time it was formally recognized by the University.

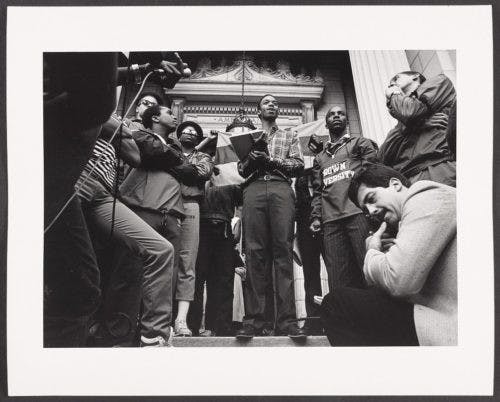

Robinson, who was an active member of Alpha Phi Alpha in the ‘80s, joined after being influenced by Black student leaders on campus such as Kenneth Elmore ’85, who helped lead the Third World Coalition’s occupation of the John Brown library in 1985, protesting the University’s alleged failure to uphold commitments made after the 1975 University Hall occupation. He was also inspired by George Bass, professor of Afro-American Studies and Theatre Arts, who founded the Rites and Reason Theatre.

“It wasn't about Alpha,” Robinson said. “It was about how Brown can be a more inclusive environment and how we can make our mark (on campus) and be excellent.”

Robinson reflected on Alpha Phi Alpha’s step dance, which they would perform at events on campus, as one memorable tradition of the fraternity. They hosted one step dance performance in Sayles Hall that was so packed that there were “people hanging off the rafters,” Robinson said.

“I regard stepping as a cultural activity, an ethnic tradition,” said Elmore in a 1985 issue of the Brown Alumni Magazine. “Originally, a step show wasn’t intended for public display; it was a means for brothers to show spirit among themselves.” Elmore added that these step dances date back to African tribes, and that brothers would often wear eyeliner or eyeshadow “because it represents tribal face painting.”

The chapter also hosted educational forums, anti-smoking campaigns and events with speakers such as actor Danny Glover and comedian Chris Rock.

“We had fewer members in Alpha when I was at Brown than we did in 1921,” Robinson said. “We didn't feel that members would limit us whatsoever … We would do major things with the small numbers we have, and we’d do it in a very impactful way.”

Members and alumni have since founded Harambee House, Inman Page Alumni Council and other spaces for Black students to gather and grow on campus, Onabanjo said.

Alpha Phi Alpha members “have constantly been thinking about Black student life and making sure that there were places where Black students could get together and just be themselves and thrive in a college environment,” Onabanjo added.

Celebrating 100 years: Alpha Phi Alpha’s persisting impact on campus

This year, the Alpha Gamma chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha celebrates its 100th anniversary.

“It is really powerful to think about the development of Black student life at Brown in the past 100 years because we were the first Black organization on Brown’s campus and even in Rhode Island,” Onabanjo said.

Since growing in membership since 2018, Alpha Phi Alpha has reestablished itself as a presence on campus, and has focused on building community for Black students.

“The chapter, from its foundation 100 years ago, was answering the question: How do we make space for Black student life on this campus in a way that feels more full?” Onabanjo said. “The chapter is still led by that same question.”

There are spaces on campus that provide Black students with resources so they are “happy enough to not complain about diversity,” but campus as a whole still does not see Black students as “full people who just want to be themselves at this school,” Onabanjo explained. Alpha Phi Alpha strives to combat that trend.

“The chapter has been one of the first signs … that Black students at this school have had to say, ‘there’s an organization here that is thinking about you directly,’” Onabanjo said. “There aren't many places on this campus that are doing that.”

In its 100 years of existence, Alpha Phi Alpha has developed many traditions and events with the goal of supporting and enriching the Black student community on campus.

They host an annual History of Black at Brown, in which alumni share their experiences as Black students on campus. At this event, students can develop their “own ideas of what it means to be Black at this school by talking with someone else who's done it at a different time,” Onabanjo said.

Each year, Alpha Phi Alpha hosts a walk in remembrance in honor of Martin Luther King, Jr., who was a member of Alpha Phi Alpha at Boston University. They also host a week-long series of events each December to celebrate Founders’ Week, with themes such as community service and Black student life, as well as 11 events during Black History Month to commemorate each of the 11 founding Alpha Gamma members.

The chapter also hosts voter registration drives, breast cancer awareness fundraisers and Black student business showcases, Onabanjo said. “Our main focus is asking what we think the Black community needs right now and finding a way to do that.”

Alpha Phi Alpha had planned a large, in-person celebration for Feb. 2 to celebrate their centennial, but it had to be postponed until at least September because of the COVID-19 pandemic, Onabanjo said. They are also hosting a monthly speaker series with chapter alumni who have become experts in their fields.

“This is something that survived for 100 years, and thrived for 100 years,” Onabanjo said. “This is a reminder to think of how we were founded and how that influences what we're doing today.”

ADVERTISEMENT