May 17, 1954 marked a landmark Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education: From that day forward, it was unconstitutional to establish racially segregated schools. In an era of Jim Crow and violent racial tensions in the United States, the court case came to be a crucial step in ending “separate but equal” ideology and advancing civil rights.

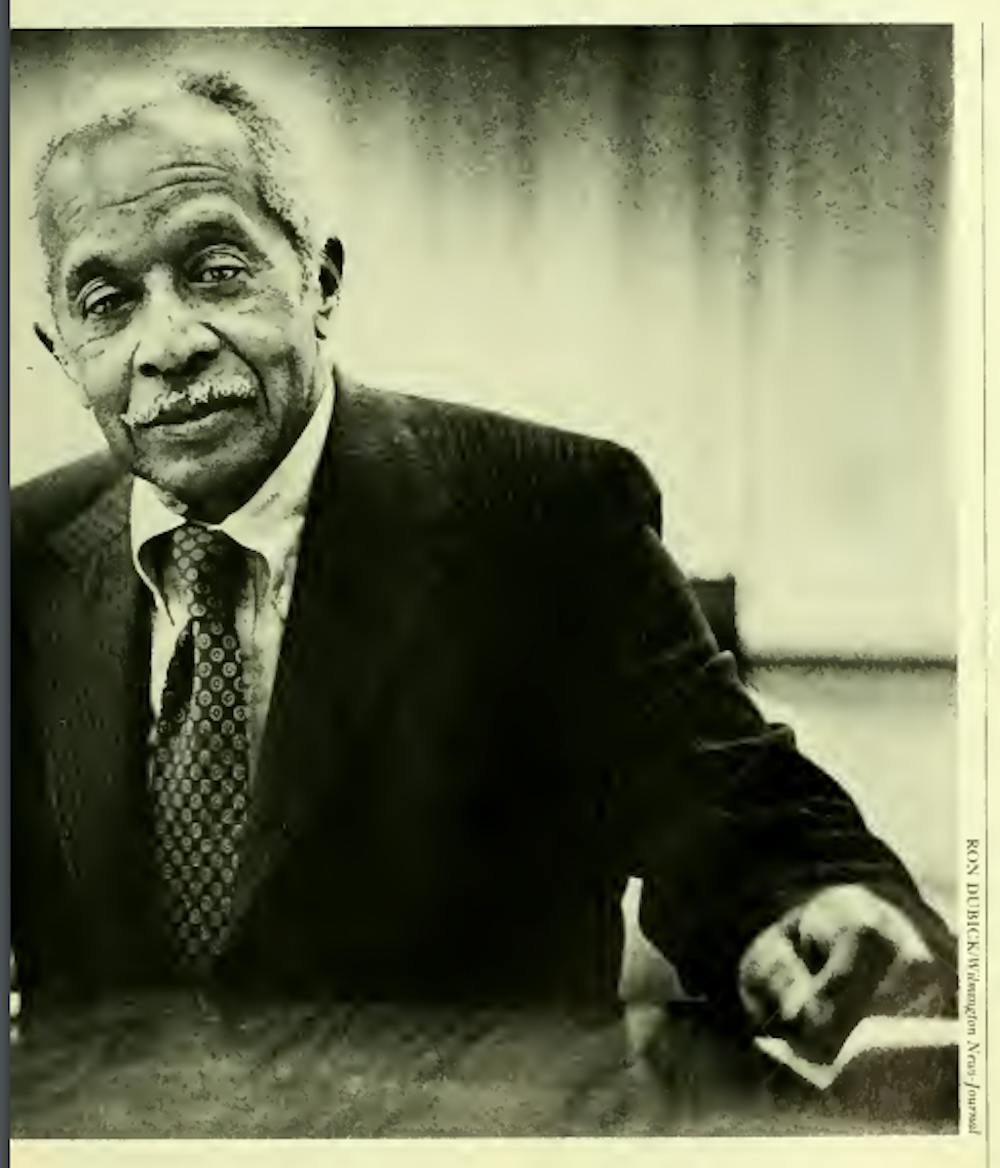

At the forefront of the momentous case was Louis Redding, class of 1923, who argued in Bulah v. Gebhart and Belton v. Gebhart. These cases, which were combined during trial, was part the other five cases that culminated in the Brown v. Board ruling, but it wouldn’t be the first or last time Redding came across the issue of racial segregation in court.

As the first Black lawyer admitted to the Delaware bar, the alum's life was punctuated by challenges against segregation, inside and outside the courtroom.

Growing up in a segregated world

Born in Alexandria, Virginia, Louis Lorenzo Redding grew up during the 1900s in Wilmington, Delaware, when the state was as segregated as the Deep South. His parents, both from well-educated upper-class families, moved to Delaware from Washington, D.C., where his father taught English at Howard University.

Redding grew up surrounded by intellectual stimulation. His mother introduced him and his younger brother, Jay Saunders Redding — a literary scholar and the University's first Black faculty member — to many classics of the literary canon, and immersed both siblings in oration.

Still, his family felt displaced in the segregated city. They were initially pushed into East 12th Street, deep in Wilmington’s East Side, before moving to a safer white neighborhood, only for that to become segregated as well, as Jay Saunders Redding describes in his autobiography, “No Day of Triumph” (1942).

Redding could only attend one school that was designated for African Americans in Delaware, Howard High School. There, he encountered firsthand the radical differences between white and Black schools at the time.

“I was acutely aware … of distinctions made in certain areas between Blacks and whites,” Redding told the Brown Alumni Magazine in 1986. “I don’t know how any kid could have had the experience of using a textbook discarded from a high school for whites without feeling he was playing second fiddle to the whites.”

Still, it was at Howard High School that Redding was able to find the inspiration that eventually led him to College Hill. In another interview with BAM in 1993, Redding said Howard had excellent teachers that were invested in its students, and that Nellie Nicholson, class of 1911 and his teacher at Howard, inspired him to come to Brown. When he left for College Hill, he added, his teachers made sure to come to the train station to wave goodbye.

During his time at Brown, Redding was one of five other Black students at the University — “the Browns from Brown,” according to BAM. He won several oratory contests and was selected to speak during Commencement in June 1923, and Redding was the president of the Alpha Gamma chapter of Alpha Phi Alpha at the University.

After graduating, Redding went on to teach English at Morehouse College in the South, before returning to New England to enroll at Harvard Law School. After graduation, he went back to Delaware to start a career as an attorney.

“I can’t say I had urged to practice law in Wilmington, but of course that’s where my parents lived,” Redding said to BAM in 1986, adding that it was because Delaware did not have any Black lawyers that his father pushed him to pursue law in his home state.

A battle in and outside of court

To get his license to practice law in the segregated state, Redding had to convince another attorney and judge to vouch for him, on top of earning perfect marks on the bar exam.

When Redding became the first Black lawyer admitted to the Delaware bar, the Wilmington Sunday Star wrote, “The ice has been broken in Delaware. Within the next year, harrying unforeseen developments, this state and particularly this city will have a full-fledged Negro lawyer …Though the present age is supposed to be living down racial prejudices, it has remained for young Mr. Redding to break through the barriers of years and years standing now.”

Throughout his career, Redding continued to face the racism he had in his youth. Excluded by the bar and viewed as “arrogant” and snobbish by other white lawyers, according to BAM, Redding was nonetheless determined not to give in to the establishment.

Redding, who was once thrown out of court during his college years for sitting on the side designated for white people, purposely told his clients to sit where they were not supposed to during court hearings. He told BAM that he didn’t want to “accept the segregation that was being fostered in a courtroom” when it was supposed to be a place “to get equal justice.”

“I suppose there was an inherent anger, but I think more than anger, one realized that he was being limited and that kind of limitation based entirely on color or race should not be,” said Redding. “So, I suppose it simply became necessary to eliminate distinction found solely on color and race. I’m pretty sure that kind of inspiration is part of my background.”

At the beginning of his career, Redding worked mostly in divorce law, criminal defense and business mergers. His first notable case was Parker v. The University of Delaware, for which Redding represented nine Black college students who were barred admission from the University of Delaware under the “separate but equal” doctrine. The court ultimately ruled in favor of the plaintiffs, making the University of Delaware the first state-supported undergraduate school to be desegregated by court order.

His most famous case, Brown v. Board, began when Sarah Bulah, a Black mother whose child could not go to her segregated school because of the white-only bus route, came to Redding for advice. This case and six others eventually merged into the landmark Supreme Court case on segregation.

His third most noticeable case was in 1958, when a Black man, William "Dutch" Burton, was denied a cup of coffee at a coffee shop in Wilmington on account of his race. The case also ruled in the plaintiff's favor, with Burton winning with the argument that his constitutional rights were violated.

Redding was never able to move on to a judicial role due to his age, and he retired shortly before passing away in 1998.

Still, his legacy is cemented in American history. The University of Delaware honored him by naming a dormitory after him, and a middle school in the Appoquinimink School District in Delaware is also named after him.

“I don’t know that I’m a hero at all,” Redding said to BAM. “I grew up with a generation of lawyers that exerted itself to abolish distinctions … wherever those distinctions were based solely on color. Of course, they should have been abolished long before. All we did was our duty, not only to the people who were discriminated against but to this so called democratic country.”

ADVERTISEMENT