Growing up, Madeline Wachsmuth ’25 remembers watching the children’s television series “Signing Time” and learning everyday American Sign Language words through the show’s catchy songs and animated segments.

So when she came to Brown as an undergraduate and began to hear about the University’s ASL program, Wachsmuth was delighted — and registered for SIGN 0100: “American Sign Language I” last fall.

The University’s ASL program had over 80 enrolled students last fall, and student interest in courses has grown over time, according to Senior Lecturer in American Sign Language Tim Riker.

Brown has offered ASL courses for over 27 years, Riker wrote in an email to The Herald. While the University considered shutting the program down in 2005, weeks of “coordinated and highly visible” student protests ensured that ASL remained part of Brown’s curriculum, The Herald previously reported. The program operates out of the Center for Language Studies.

Today, Brown’s ASL program has two faculty members, both of whom are deaf, and offers four levels of language classes along with an independent study in Sign Language/Deaf Studies.

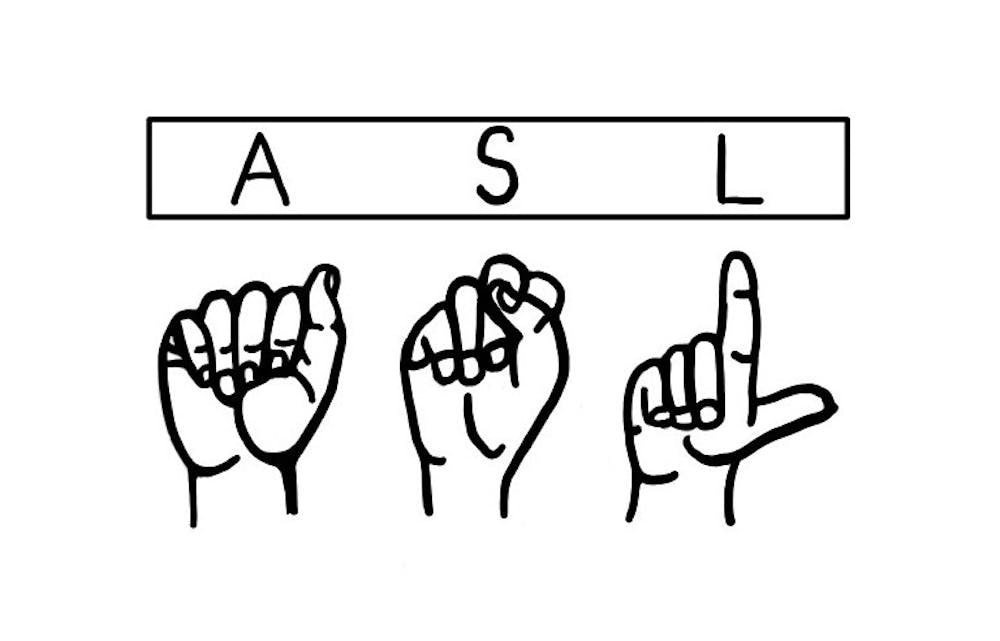

Because ASL is a visual language rather than a spoken one, it makes for a unique classroom learning experience, Seehanah Tang ’25 told The Herald.

Tang remembered an interpreter being present during the first few classes of SIGN 0100. But “after learning some basic words and the alphabet to spell things out, we were able to communicate” without an interpreter, Tang said, noting that she was “immersed in a completely quiet environment.”

“Whenever I see other people in my class on the street, we sign to each other,” she added.

Riker wrote that he is proud of “the dedication of (the program’s) faculty and students,” as well as the program’s “resilience and adaptability” in the face of the COVID-19 pandemic.

The pandemic “required us to quickly adapt our curriculum and teaching strategies to an online format to keep students engaged and learning,” Riker explained.

And when students returned to class with masks on, it “presented a new set of pedagogical challenges, particularly in teaching and evaluating students' facial grammar,” he added.

Riker said that the ASL program strives to keep its content relevant and expose students to the lived experiences of the Deaf community as they navigate the pandemic — during which limited information has been available in ASL.

When his father, who is deaf, passed away during the pandemic “without access to health care or the ability to comprehend what was happening to him,” Riker wrote that he “realized the importance of advocating for the Deaf community's civil and human rights to language and education equality.“

“The world is facing various crises, and it is essential for us to come together and find solutions,” he wrote. Program “alumni have used what they learn … to work on making the world a more just and equitable place.”

Wachsmuth has already begun using the skills she’s learned through the University’s ASL program outside of the classroom. When she was volunteering for a local street-church community Church Beyond the Walls, Wachsmuth met a deaf, unhoused person and was able to communicate with him through ASL and get him a pair of shoes.

“He was signing or trying to gesture to people to communicate what he needed,” she said. “I had barely just started learning ASL, but I was able to sign out a ten-and-a-half.”

“I also learned that it was his birthday, and it just made his day to have someone he could communicate with,” Wachsmuth added.

Camille Aquino ’24, a teaching assistant for SIGN 0200: “American Sign Language II,” said she hopes to apply her knowledge of ASL to her future career in medicine.

“I want to know how to work with patients from special populations,” she said, referring to a term used by the federal government and among medical practitioners. “We have to be conscious when we're trying to provide care for them.”

Aquino currently teaches first graders at the Rhode Island School for the Deaf and tutors adult deaf students with mental or developmental disabilities.

Students interested in gaining a deeper understanding of sign languages and the communities that use them also have access to the Brown Sign Languages Society, which engages with the Providence Deaf community by hosting speakers, coffee chats and workshops.

For Wachsmuth and Riker, ASL is about more than just learning a new language — it’s about helping others and gaining a new understanding of a complex and diverse world.

“It's not just for you to go around using for your own gain or resume,” Wachsmuth said. “You need to have that respect and understand the context in which it's in.”

“In the end, learning ASL teaches us that we are all human and that we each make valuable contributions to the world in our own way,” Riker wrote. “By embracing new experiences and perspectives, we become richer, more empathetic individuals.”

Harry is a staff writer for The Brown Daily Herald. Harry is a sophomore from Beijing, China majoring in ceramics at RISD.