Whether it’s football players colliding on the field or military personnel exposed to explosive blasts in combat, traumatic brain injury is a prevalent — and potentially deadly — condition responsible for tens of thousands of deaths in the United States per year.

Yet despite its severity, the long-term effects of traumatic injuries on the brain are not fully understood, said Haneesh Kesari, an associate professor of engineering.

“We talk about all sorts of diseases — say fevers, infectious diseases, viruses — but something that doesn’t seem to be thought of as much as disease is something that is triggered by mechanical forces,” Kesari said. “The biology and the physiology (are) not well studied.”

Limitations in this field may stem largely from biological reasons, as the brain lacks pain receptors that call attention to potential damage, Kesari said. These injuries can arise from high-impact activities including football, military exercises and high-speed motor boat rides.

With these challenges in mind, Kesari’s applied mechanics research team has been developing an innovative wearable helmet designed to detect the impact of traumatic events on the brain. Known as the “accelo-hat,” the helmet consists of sensors that can measure the acceleration of the head following impact. When the data is applied to a virtual model of the head, the team can determine the effects of the impact on the brain’s anatomy.

Kesari’s research was conducted within the PANTHER initiative, a national research program aimed to improve detection and prevention of traumatic brain injury, according to their website. The initiative was started in 2017 by Christian Franck, who was then an associate professor of engineering at Brown when the U.S. Department of the Navy’s Office of Naval Research provided a $4.75 million grant to the University.

For the Navy, the push for research like Kesari’s comes amid a time of growing concerns about the safety of the branch’s Special Boat Teams. These teams ride stealth boats at high speeds, which can result in repetitive impact from crashing into the ocean’s waves, causing neurodegenerative disease in some sailors.

“When (the Navy) asked me to look into this problem, we saw that there are all these devices in the market, but then I realized that the data given by these devices is not enough to figure out what is happening in the brain,” Kesari said.

To test their device, Kesari’s lab recruited participants at numerous Navy bases. The team also created a full-size dummy — named the “Accelo-Randy” — to evaluate their sensor technology in situations unsafe for human testing, such as riding a military stealth boat. Composed of 11 bodily sensors, the “Accelo-Randy” can mirror the impact of trauma on the human head. These efforts culminated in a lab presentation of their findings and technology at the White House in 2023.

The team also collaborated with other Brown researchers including Diane Hoffman-Kim PhD’93, an associate professor of medical science and engineering. This partnership helped both labs understand the corresponding biological consequences of traumatic injuries at the cellular level.

Hoffman-Kim’s lab created “mini brains,” small clusters of cells taken from the brains of mice which are then cultured and clumped to create a representation of a normal human brain. These mini brains, composed of 3,000 to 8,000 cells, are “really good stand-ins for brains,” which normally consist of approximately 86 billion neurons, Kesari said.

Compared to traditional methods that directly apply mechanical forces to the heads of live mice, the mini brains enable researchers to apply small-scale, calculated forces by loading the mini brains into a fast-spinning centrifuge at varying speeds, Kesari said. As a result, the team can determine the level of forces that result in cellular damage in the short- and long-term, he added.

Beyond Kesari and Hoffman-Kim’s involvement, Associate Professor of Engineering David Henann and his lab have contributed to the PANTHER initiative by modeling the safety of foam liner materials in combat helmets using mathematical optimization and computer simulations.

“One of the things that has been very beneficial to this project, in particular, has been the tight collaboration with industrial collaborators who are in the business of producing combat helmets that are used by the military,” Henann said.

For Henann, his involvement in PANTHER has been rewarding because of the opportunity to apply his personal research interests in modeling material physics to an evolving, innovative field.

“The work is ongoing,” Henann said. “New threats are always being identified, and that motivates research problems.”

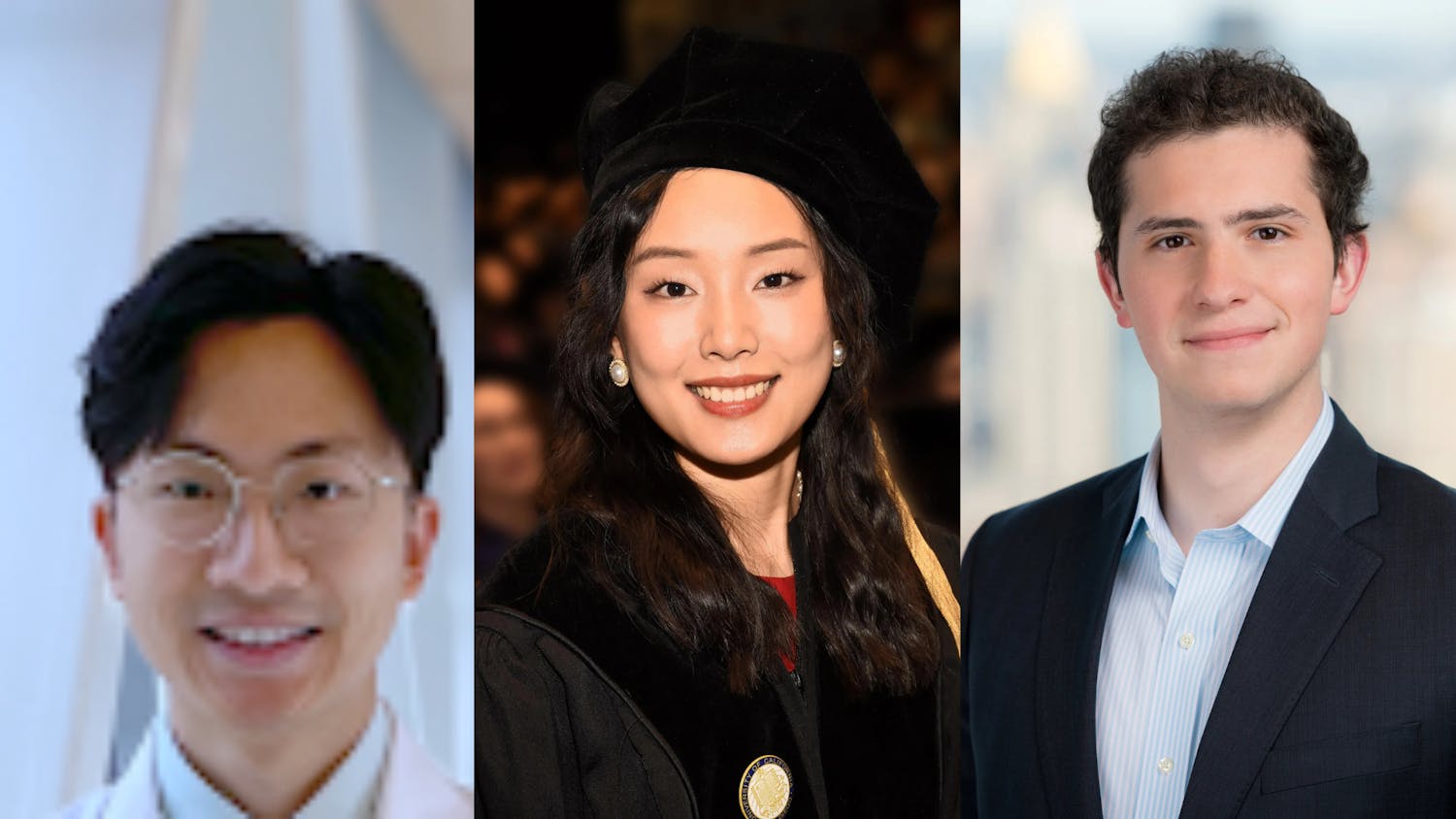

Jonathan Kim is a senior staff writer covering Science and Research. He is a second-year student from Culver City, California planning to study Public Health or Health and Human Biology. In his free time, you can find him going for a run, working on the NYT crossword or following the Dodgers.