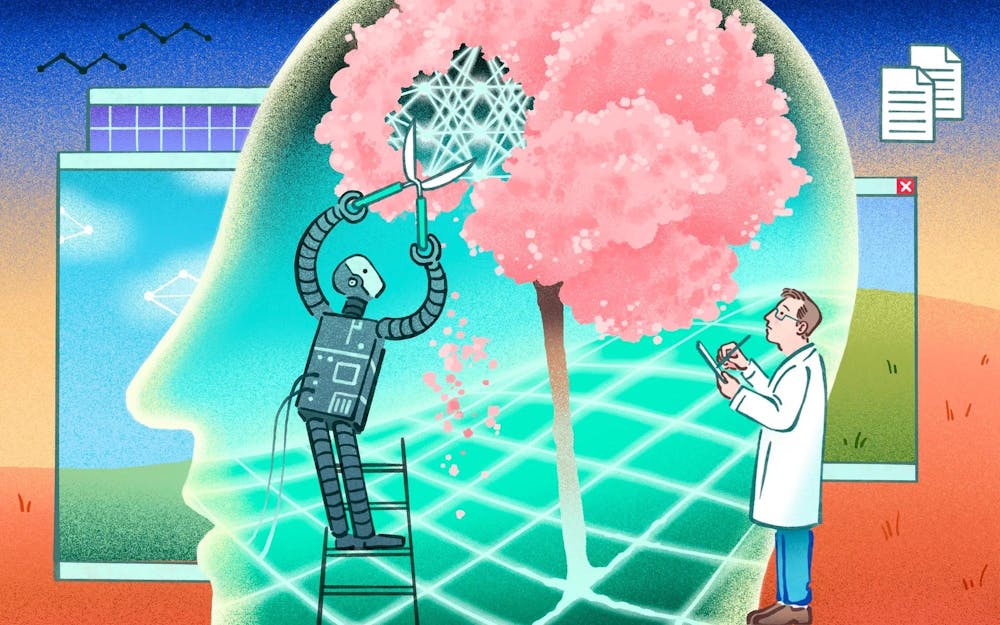

As artificial intelligence takes science by storm, two Brown researchers who study cognitive and psychological sciences and computer science predict that self-supervised learning, which plays a crucial role in training the large language models that underpin AI platforms like ChatGPT, will transform the neuroscience field.

Neuroscience is a field with “some of the greatest mysteries in science,” Ellie Pavlick, associate professor of computer science and cognitive and psychological sciences, said in an interview with The Herald. According to Pavlick, AI foundation models — large AI systems trained using self-supervised learning on vast, unlabeled datasets — hold great promise for analyzing neuroscience datasets, such as parsing through human neuroimaging data or identifying biological markers for conditions like obsessive compulsive disorder or depression.

A Neuron paper by the Brown researchers — Thomas Serre, professor of cognitive and psychological sciences and computer science, and Pavlick — examines how deep-learning approaches will enable higher accuracy and capability in neuroscience research, particularly in the realm of predicting human decision making.

Pavlick and Serre hone in on the concept of digital twins — AI models that may be able to reflect human neural or behavioral data.

“If you’ve interacted with AI systems, you know they act very human a lot of the time,” Pavlick said. “That makes it feel like they should have something to say about how humans achieve those same behaviors.”

Uncovering how digital twins work mechanistically “under the hood” could unlock how the brain works, Pavlick explained.

“If you can build up a kind of a theory of the AI system, then this theory becomes an interesting candidate theory for what’s happening in humans,” she said.

For AI to truly be groundbreaking for neuroscience, Pavlick asserted, it is essential to understand how the machine itself works — a puzzle that scientists have not yet completely cracked. While computer scientists understand the mathematical side of the AI system, they do not yet understand what Pavlick would call the “cognitive theory.”

“Now there’s two things we don’t understand instead of one thing,” Pavlick said, referring to the brain and the AI model. “You can’t explain one black box with another black box,” she added.

Additionally, even if researchers did completely understand how the neural networks behind the AI models function, there are still limitations to what they may reveal about their human counterparts. While foundation models can often successfully predict neural responses, predictive accuracy alone does not constitute a scientific explanation for what these responses entail, Pavlick and Serre noted.

These models generally can very accurately predict human neural or behavioral responses, but “that doesn’t mean that the mechanisms that are used by (the) model match those of the true ones that are happening in your brain,” Serre explained in an interview with The Herald.

Michael Lepori GS, a doctoral student advised by Pavlick and Serre, said that “in terms of practical tasks,” foundation models are “very good.” But, Lepori said, it’s still “up in the air" whether these models will actually tell us anything about the domains they’re modeling.”

The models “could just be statistical pattern matchers,” he added. “It’s an open research question.”

To answer these questions, Pavlick said that she and her colleagues are studying the two systems — the brain and the AI model — concurrently to decipher the similarities and differences between the two.

“It could be that AI is doing exactly the same thing humans do,” Pavlick said. But she finds that “extremely unlikely.”

But given the extraordinary ability that AI foundation models have displayed to behave like humans, Pavlick finds it likewise “pretty unlikely” that there is no resemblance between the processes. Most likely, in Pavlick’s view, scientists will find that AI models employ some similar tools as human cognition but also some completely different mechanisms.

“The real challenge for us humans,” she said, “is deciding whether we want to call both things thinking.”

Amrita Rajpal is a senior staff writer covering science and research.