Surfactants derived from shea butter, an ingredient found in many skin care products, may remediate contaminated water. The compounds can effectively remove polyfluoroalkyl substances, also known as PFAS, from polluted water, Brown researchers found.

PFAS have been utilized in consumer products since the 1950s, according to Joseph Braun, director of the Center for Climate, Environment and Health and professor of epidemiology. Now, the compounds are dubbed “forever chemicals” because of their environmental presence and persistence.

The chemicals have also been linked to adverse health effects, including reduced fetal growth, reduced vaccine response, elevated cholesterol levels, liver disease and higher risk of prostate and testis cancers, Braun wrote in an email to The Herald.

Foam fractionation is a separation method that uses air bubbles and co-surfactants to cleanse PFAS-contaminated water. But current methods involve the use of toxic chemicals.

“You’re solving the PFAS problem, but the last thing you want to do is replace it with a new one,” said Craig Klevan MA’23 PhD’25, an author of the paper.

So, using products proven to be safe for humans was a main focus of the study, Carolina Gomez Casas GS, an author of the paper, explained.

When exploring less toxic alternatives, the team looked to FDA-approved food additives and cosmetic ingredients, which had already been screened for toxicity and safety, Klevan said.

The shea-derived positively-charged co-surfactant was less toxic than conventionally used chemicals and was only toxic at the highest concentration, Gomez Casas said.

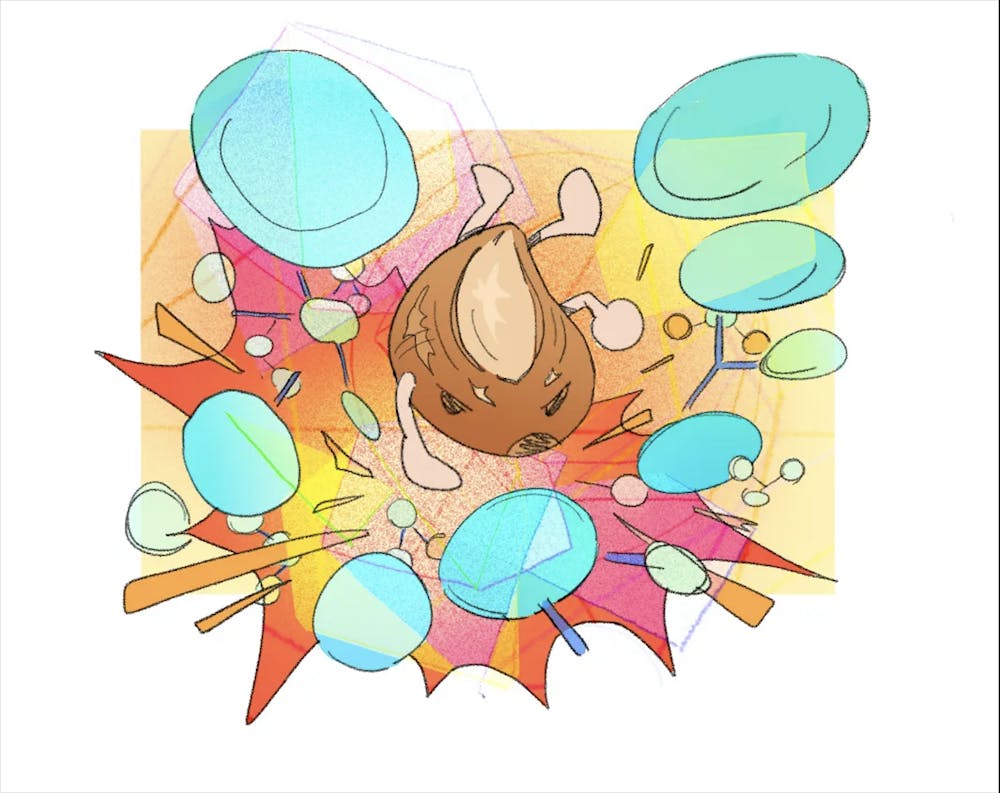

PFAS have a hydrophobic carbon-fluorine chain, which repels water, and a hydrophilic head group, which attracts water, contributing to its surface active properties. Klevan explained that the new foam fractionation method “takes advantage” of this differential affinity for water by adding air bubbles to PFAS-contaminated water.

When the short-chain negatively-charged PFAS bind ionically to the positively charged shea-derived polymers, this creates an “ion pair,” explained Kurt Pennell, an author of the paper and professor of engineering.

The “ion pair” then latches onto the bubbles as they rise, allowing for the extraction of the ‘forever chemical.’

This works well enough for longer PFAS, Pennell said. But shorter ones pose a problem — they’re not as hydrophobic so they don’t rise to the surface for removal.

Looking forward, the team will look to create a mathematical model to predict the efficiencies of certain surfactants, Pennell said.

Because there are already foam fractionation systems in place, Pennell said that the barrier to industry implementation is not necessarily technical. Instead, it is integrating into the existing surfactant economy.

“That’s a barrier to anything you develop,” Pennell said. “Even if it works better, there’s resistance sometimes.”

Nishita Malhan is a senior staff writer covering science and research.