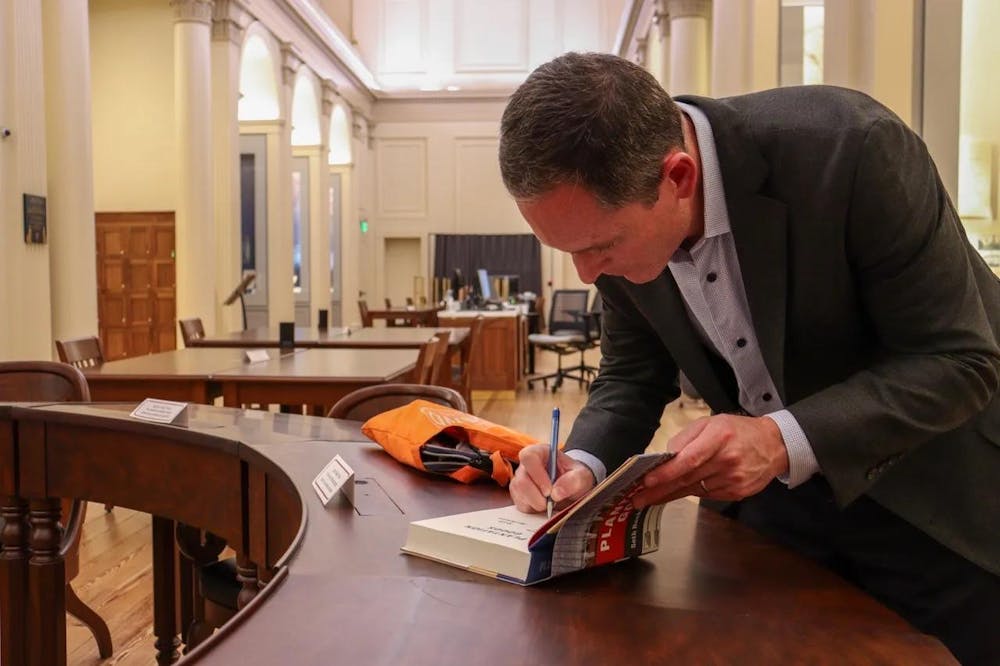

In May, Professor of History Seth Rockman learned his 2024 book “Plantation Goods: A Material History of American Slavery” was named as a 2025 Pulitzer Prize finalist at the same time as everyone else — when it was announced live on broadcast.

“I didn’t even know that that was happening that day, and I was actually teaching a class here at Brown when this was announced,” Rockman said. “My phone started buzzing like crazy in my pocket because so many friends were texting me to say ‘congratulations.’”

The recognition, he said, is “the kind of thing that academic dreams are made of.”

But receiving a Pulitzer Prize finalist nomination in the history category was just one of the accolades “Plantation Goods” received. The book was also a finalist for the Mark Lynton History Prize, which celebrates books of narrative history, and it was one of 15 books longlisted in July for the Cundill History Prize administered through McGill University.

“Plantation Goods” also won this year’s Philip Taft Labor History Book Award, presented by Cornell’s School of Industrial and Labor Relations, making Rockman a two-time winner. His previous book, “Scraping By: Wage Labor, Slavery and Survival in Early Baltimore,” won the prize in 2010.

The term “plantation goods” refers to the “very mundane things” — such as shoes and shovels — manufactured in 1800s New England that supported the American South’s “economy of slavery,” Rockman explained. In the book, Rockman traces the paths of these goods from the North to the South, as well as their connections to “opportunity and oppression” in the U.S.

Rockman noted that the book, which took more than 15 years to write, explores these goods through a variety of perspectives.

“These goods might mean one thing to a New England mill worker who’s confronting the transformation of their life into wage labor,” Rockman explained, “and might mean something incredibly different to an enslaved seamstress who is tasked with sewing New England-made fabric into clothing for the men, women and children held in bondage on the same plantation.”

The idea for the book was born after Rockman’s involvement in creating the University’s Slavery and Justice Report in 2006.

“It was my hypothesis that New England’s relationship to slavery didn’t simply end when the slave trade ended, but rather became different and took different forms,” Rockman said. “And so this book was a way of, in some sense, following up on the kinds of stories that you would find in the Slavery and Justice Report.”

While historical research typically involves studying letters, business records and other archival documents, Rockman said his research for this book took a more hands-on approach since he was studying material artifacts themselves.

“By looking at the design of a shoe, or looking carefully at the … weave structure of a given piece of cloth, you could learn some other things,” Rockman said. “And that’s one of the ways in which I was able to tell a bigger story, and a more complicated story, than I would have been able to if I had just used written records.”

In addition to studying the material artifacts, Rockman devoted some time to conducting experiential research, like learning how to weave. He went to a school of historic weaving to recreate fabrics produced in New England two centuries ago, using archival records as a guide.

“Public historians and museum professionals are benefiting enormously from this book because of the objects as sources,” said Rebecca Brenner Graham, a postdoctoral research associate for the Brown 2026 initiative. “Many museums interpret objects, so it’s just invaluable for their work.”

Rockman incorporated this material research into HIST 0552A: “A Textile History of Atlantic Slavery,” a first-year seminar he began teaching in 2021 that explores clothing as “a mode of self-expression for enslaved people,” he said.

“We had some really awesome discussions, and the reading list was super robust,” said Ellanora LoGreco ’27, who took the class in her first semester at Brown. “He’s so excited and happy to help students, especially when their interests align with his specific areas of study.”

Reflecting on his career, Rockman said he is especially proud of the success of his students. “To look at people who I’ve had the chance to teach … and see them go out into the world and do amazing things is the kind of thing that fills my heart at the end of the day,” Rockman said.

“For someone who is such a high-powered and celebrated historian, he is an extremely down-to-earth mentor,” said Nicholas Gandolfo-Lucia GS, a history PhD candidate. “It can’t be overstated how unique that is when you spend time in academia — those are not things that normally go hand in hand.”

Karin Wulf, history professor and director of the John Carter Brown Library, described the book as an “incredibly impressive work of deep and close research” that was also “so well-written.”

Rockman has already begun his next work: a book about the U.S. spanning from the American Revolution through the 1840s that examines “the new United States alongside nations that, in more recent times, we think about as developing nations,” he said.

Correction: This article has been updated to accurately reflect Rebecca Brenner Graham's title.

Ivy Huang is a university news and science & research editor from New York City Concentrating in English, she has a passion for literature and American history. Outside of writing, she enjoys playing basketball, watching documentaries and beating her high score on Subway Surfers.