Whether it’s under the stars on the Main Green, from smudged dorm windows or through open sunroofs, we see the moon nearly every night. But a new study by Brown researchers suggests that we know less about the formation of this familiar celestial sight than previously thought.

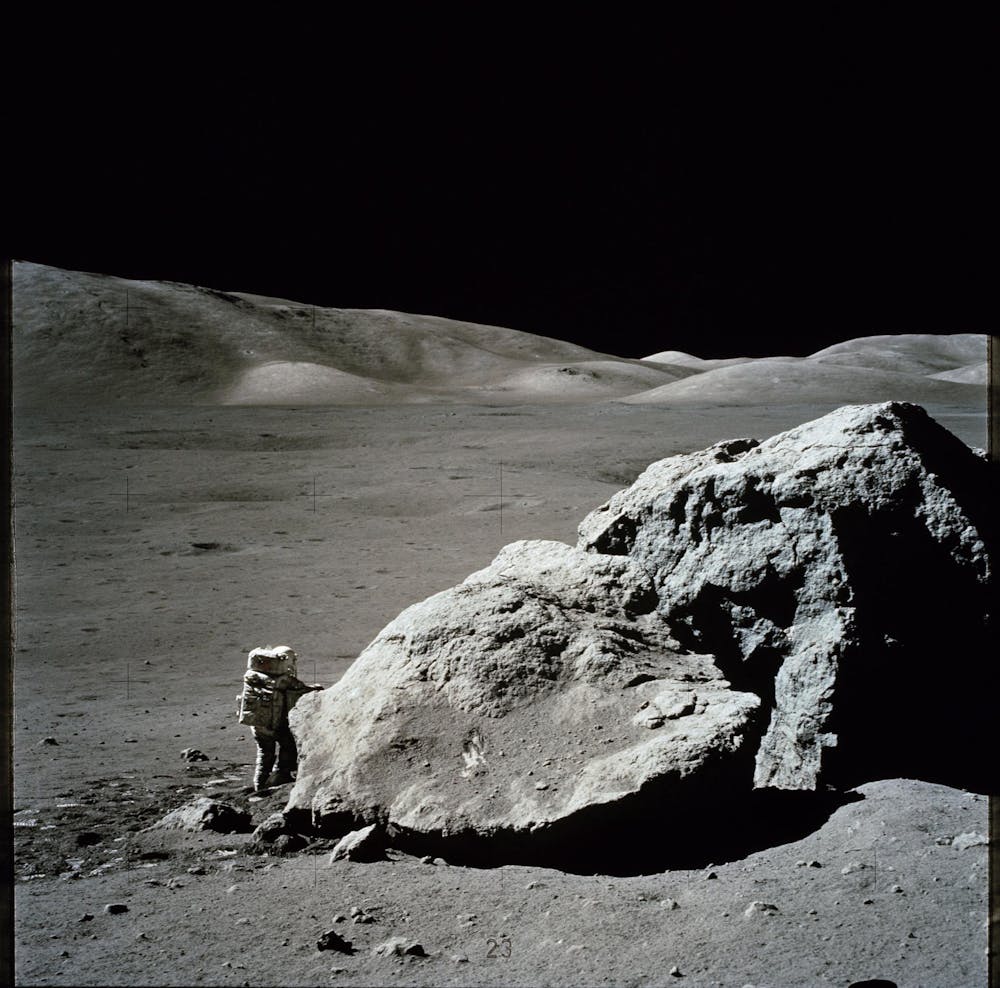

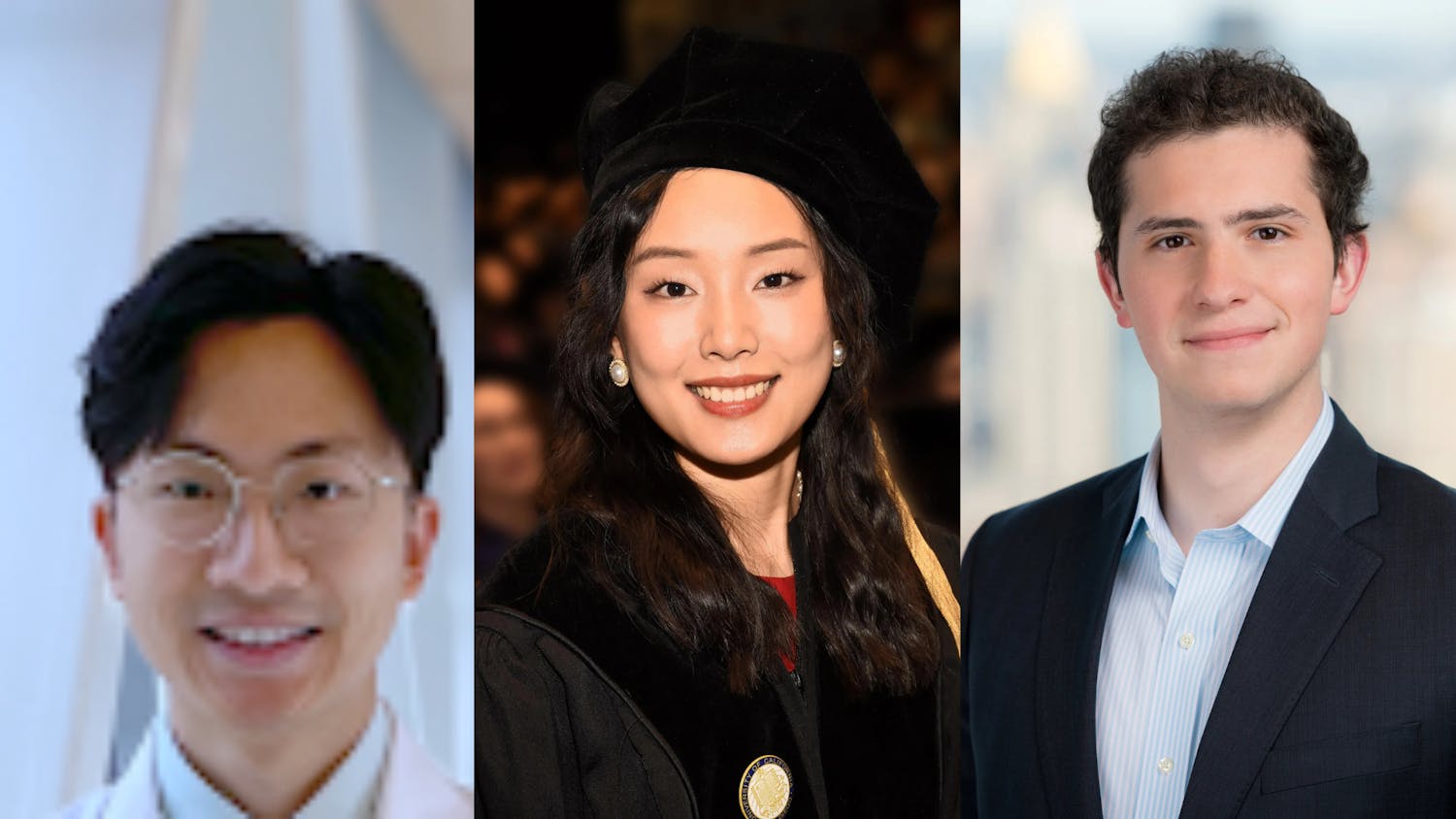

The study, led by Assistant Professor of EEPS James Dottin III, analyzed a core sample from the moon’s surface collected during the 1972 Apollo 17 mission, NASA’s most recent crewed mission to the moon.

This particular Apollo iteration was the only one to carry a geologist onboard, which “helped Apollo 17 retrieve many of the very interesting samples that people have been analyzing for roughly 50 years,” said Hairuo Fu, a postdoctoral researcher in Earth, environmental and planetary sciences who co-authored the study.

The results of the core analysis, Dottin said, diverged from expectations. Certain sulfide minerals within the sample had much lower levels of sulfur-33 than predicted — a finding that could upend longstanding theories about how the moon formed.

Prevailing wisdom about the moon’s formation centers on the “Giant Impact Hypothesis — the idea that a Mars-sized impactor hit the proto-Earth very early in the solar system’s history … shattered it and sent a disc of material around it, from which the moon formed,” said Stephen Parman, a planetary geochemist and professor of EEPS.

Most models predict that “the moon was completely molten when it formed,” meaning the Earth and moon should share nearly identical isotopic reservoirs, Parman added. But the sulfur anomaly suggests otherwise.

On Earth, the natural abundance of sulfur isotopes follows certain patterns — sulfur-32 is by far the most common, while sulfur-34 appears in roughly 4% of sulfur atoms and sulfur-33 is present in less than 1%. Stable-isotope geochemists use deviations from these patterns to track planetary processes and even primordial materials.

Past studies on lunar geology used “bulk analysis” methods, where researchers “homogenized” all the sulfur extracted from a particular lunar rock sample before inspecting its isotope ratios, Dottin said. These methods yielded similar compositions as those seen on Earth, which “told us that the Earth and the moon share a common sulfur source,” he added.

“But, as we published in the paper, that’s not what we found,” he said.

In contrast, the recent Brown study utilizes “micro-analytical techniques,” focusing on individual sulfide grains, Dottin said. The team sorted fine particles of lunar soil, polished them into sections, then used a secondary ion mass spectrometer to vaporize the individual grains and measure their sulfur-isotope ratios.

The relative depletion of sulfur-33 in lunar sulfides, according to Dottin, suggests one of two possibilities: Either exotic sulfur-bearing material from farther out in the solar system contributed to the formation of the moon, or early lunar surface-atmosphere chemistry significantly fractionated sulfur isotopes.

One alternative hypothesis is that the moon incorporated planetary building blocks from far beyond the inner solar system — perhaps material that retains a non-terrestrial sulfur signature, according to the study. Another hypothesis is that the moon once hosted surface processes, or even a transient atmosphere, that altered sulfur isotopes, and those chemical fingerprints were preserved in volcanic or interior materials.

According to the researchers, the study underscores why lunar samples from decades past remain crucial scientific material: They offer access to parts of planetary history that Earth’s active geology erases.

“Stable isotopes and magmatic processes… (let) you see further back to the origin of the moon and what parts it’s being made out of,” Parman said.