There’s little Janaya Kizzie loves more than history.

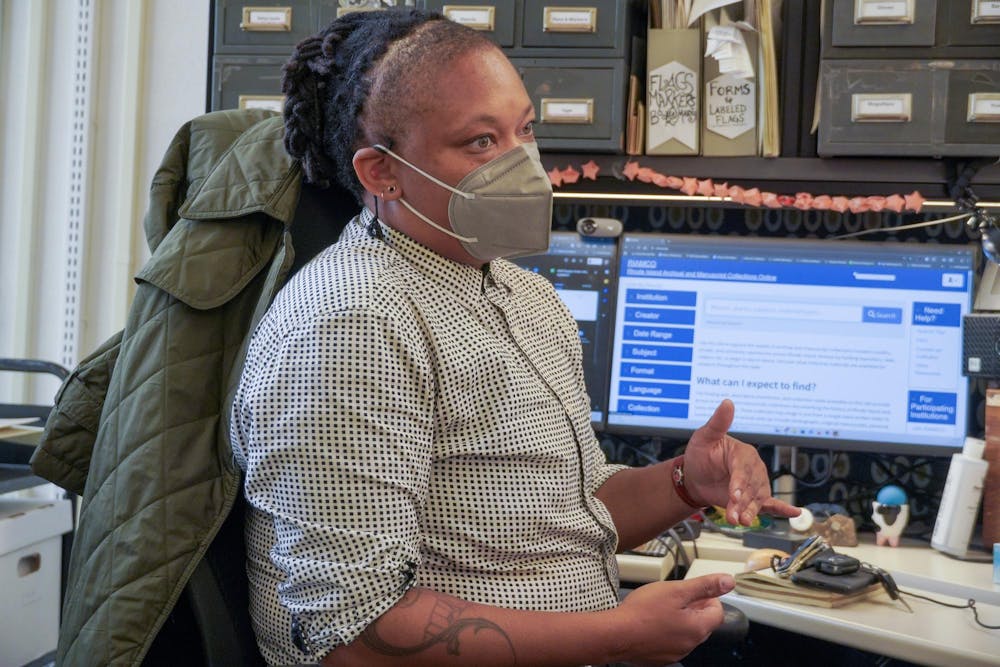

And, as a processing archivist at the John Hay Library, Kizzie gets to immerse themself in it every day.

Kizzie joined the Hay’s archival team almost four years ago, but for the past 20 years, they have been surrounded by library stacks.

“Becoming an archivist was really a big part of my artistic practice,” Kizzie said. “There’s so much inspiration, so much of the human experience that you get to see in these minute details.”

Archivist is an umbrella term: At the Hay, there are entire teams of curators, accessioners, records managers and reference librarians who each handle different stages of acquisition and preservation. As a processing archivist, Kizzie is responsible for the handling, preservation and cataloging of acquired or donated materials.

“When things come to us, they’re often in a very raw state,” Kizzie said. “I do any immediate conservation work to make sure items that are moldy or damaged are fixed and prepared for long-term storage.”

Afterwards, they create cataloging records and a finding aid — a document detailing a full inventory of items in the collection. The goal is to create an organized database researchers can easily access and pull from.

Every day at the Hay looks different, but Kizzie always begins their morning the same way: by checking emails. While Kizzie joked that most of their job takes place “inside of a locked vault,” they still get many questions from students, researchers and the general public about the collections.

Kizzie usually spends the rest of the day on “processing time.” In order to understand a collection holistically, they explained, “you need long periods of uninterrupted work time.”

For Kizzie, being an archivist means preserving the human story.

In the center of their office is a cluster of tables where Kizzie physically handles the materials. With bare hands, not white gloves, Kizzie noted — something the movies always get wrong, they added. Processing time is Kizzie’s favorite part of the day, since “it’s monastic and quiet, repetitive but thoughtful work.”

Usually, they’ll listen to music as they work: pop or Slayyyter. “Once it gets to winter I will probably get back into metal,” they added.

When asked what their favorite smell in the archives was, they immediately responded: “Old leather books.” The paper’s breakdown produces the same chemical that’s in vanilla, which “creates this really lovely smell,” they added.

Right now, Kizzie is reprocessing the Martha Dickinson Bianchi and Mary Landis Hampson collection, which contains materials related to Emily Dickinson’s family. The process involves creating a thorough inventory, conservation assessment and historical and biographical notes.

At the Hay, archives are split into two broad categories. Among the first are manuscript collections, which include research materials from a wide range of people and communities. Kizzie has worked on the papers of Joy Harjo, the first Native American U.S. poet laureate, and the quilt from the Annmary Brown Memorial.

“Sometimes it’s literally an iPhone that we pull the files off of,” Kizzie said. “Sometimes it’s somebody’s entire Google Drive.” Kizzie’s colleague, Hilary Wang, handles most of these materials as the Hay’s digital archivist.

The other category of archives is University-related. This includes records from the President’s Office, “an incredible collection of Brown swag,” publicity photos and even student films.

“Respect des fonds” is the principle of archival theory that Kizzie and their team adhere to. For them, this means “keeping original order” and respecting the creator’s intended organization of the archived material. All changes to the materials’ structure are documented in an effort to provide future researchers with a holistic understanding of the archive and its history.

Kizzie still finds themselves in awe each day, even after 20 years in the field.

Before coming to Brown, Kizzie “worked some really miserable retail jobs.” But they eventually got a job as an assistant at Princeton’s Special Collections at the Seeley G. Mudd Manuscript Library.

For Kizzie, being an archivist means preserving the human story. But this preservation work is not only physically intense — standing at a table sorting materials for hours at a time — but emotionally draining as well.

“There’s actually a lot of work happening in the archives world right now to talk about the emotional labor involved in working in archives,” Kizzie said. There is an expectation that archivists are “withdrawn” and “neutral,” when really, it is impossible not to get emotionally invested in the materials and stories archivists are responsible for.

“Libraries aren’t neutral, and the labor that’s being done has a cost,” they added.

Kizzie pointed to the work they’re doing on preserving materials related to the Dickinson family. Emily Dickinson’s nephew died at a very young age, and “going through the papers, you can see letters being sent between family members, including his,” they explained.

“You can see how utterly loved and cherished this child was right up until he died,” Kizzie said. “And it’s incredibly moving.”

After a day spent in the stacks, Kizzie finally gets to decompress at their home in East Providence. Their current obsession — the TV show “The Gilded Age” — surprisingly gets “a lot right” about the 1880s.

Beyond television, Kizzie recently “got into puzzles” — the three-dimensional ones are their specialty. Since real plants aren’t allowed in their office, Lego versions cover their desk instead. Kizzie and their colleague Wang have also decorated the stacks with local artwork.

Reflecting on the current state of their field, Kizzie worries about the ways in which the modern world will be preserved — unlike leather books of the past, paperbacks fall apart after about several decades. But they acknowledged that the formal archival process isn’t always the best means of recording the past.

“There’s lots of ways of transmitting history, and people should choose the way that is right for them and their communities,” Kizzie said.

Currently, the archives are missing many histories of marginalized groups. “Archives were meant for holding formal records, and formal records are often the tool of the oppressor,” they said.

Kizzie said the Hay is “trying to fill in those silences” by seeking out materials from historically oppressed groups, such as its recent acquisition of costumes from Spiderwoman Theater, a performance troupe of Indigenous women that used storytelling traditions to create original works.

Kizzie still finds themself in awe each day, even after 20 years in the field. Many archivists get giddy when handling rare or impressive works — whenever a researcher requests the Hay’s copy of “The Birds of America,” a book by John James Audubon featuring original illustrations of hundreds of birds, a message is sent out to the entire library staff so that everyone can see it again.

“It’s just amazing to see that the people of the past lived so similarly to the way that we do,” Kizzie said, “to understand them and to understand the differences too.”

Correction: A previous version of this article misspelled Slayyyter and Hilary Wang. The Herald regrets these errors.

Maya Nelson is a university news and metro editor covering undergraduate student life as well as business and development. She’s studying English on the nonfiction track and loves to read sci-fi and fantasy in her free time. She also enjoys playing guitar, crocheting and spending an unreasonable amount of time on NYT Spelling Bee.