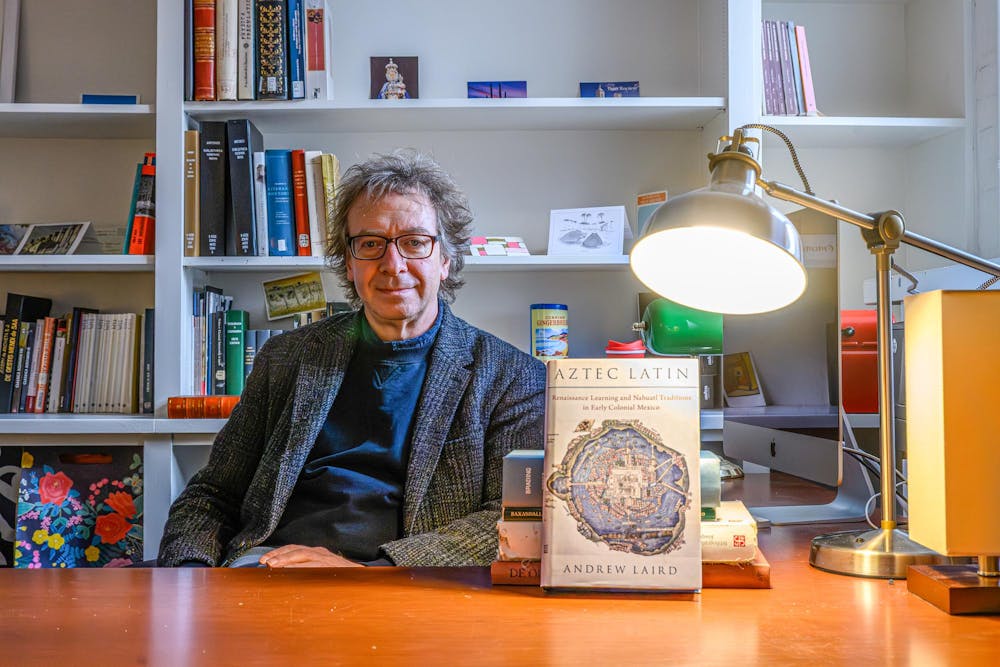

Late last month, Andrew Laird, professor of Classics and humanities and Hispanic studies, learned that his 2024 book “Aztec Latin: Renaissance Learning and Nahuatl Traditions in Early Colonial Mexico” won the 2025 Miriam Usher Chrisman Prize for History.

Awarded by the Sixteenth Century Society, the prize recognizes high-quality and innovative books focused on the early modern period, which spans from around 1450 to 1750.

In the book, Laird explores how Renaissance humanism — introduced by Franciscan missionaries after the Spanish conquest of Mexico in 1521 — became the bedrock for the education of Indigenous elites, who used “Latin as a vehicle of communication for their own purposes.”

“They weren’t just obediently translating Christian material,” Laird told The Herald. They “also used the Latin language for petitions and to write histories from oral memory of their own pre-Hispanic past.”

The award has “been a very nice surprise,” Laird said.

“I am delighted, particularly because it shows that people who study Latin aren’t only … relevant to Classics departments,” he added.

José Montelongo, the curator of Latin American books at the John Carter Brown Library, applauded the book for its importance in defining scholarship about the time period.

“It is among the most remarkable recent contributions to our understanding of 16th-century Mexico,” he said. “I would be hard-pressed to think of a period that is more consequential for Mexican history than the radical transformations of the 16th century, and the education of indigenous nobility is an important element of those transformations.”

The idea behind “Aztec Latin” arose when Laird came across colleges, monasteries and convents built in the 1500s and 1600s, as well as Baroque music, on a trip to Mexico years ago.

“It occurred to me that if there was that level of art, architecture (and) music, that there had to be a culture of learning,” Laird said. “That was what made me interested to see if I could find scholarship and books written in Latin.”

For Associate Professor of History Jeremy Mumford, the book’s importance comes from how it shows “the complex character of colonialism and the way people bought into it.”

When Laird arrived at Brown, he “was one of the only people — and certainly the best scholar in the world — who worked on” how European classical civilization affected the Americas and indigenous society, Mumford added.

But there has been some pushback to “Aztec Latin” from other scholars. According to Laird, some critics disagreed with his argument that the study of Latin literature was what led native scholars to develop a “sophisticated literature in Nahuatl,” a indigenous language in Mexico. Others criticized his identification of European sources in “Nahuatl texts that have long been considered to be of purely Indigenous origin,” he explained.

But Laird noted that “it’s very important not to be patronizing, not to be condescending and not to idealize Indigenous scholars in the 16th century as having only drawn from their own legacies.”

There were four languages involved in the creation of “Aztec Latin”: Latin, Nahuatl, Spanish and the English that the book is written in, according to Laird.

He hopes readers of “Aztec Latin” realize that “it’s very important for languages to have a place in humanities education, and in all education, or we’ll end up living in insulated, atomized worlds,” he said.

While conducting research for “Aztec Latin,” which took 10 years to write, Laird believed that to do “this project on Mexican Latin properly,” it was important “not to turn to Mexico only armed with a classicist’s toolkit.”

In his research, Laird pulled from multiple archives, including the National Library of Mexico, the General Archive of the Indies in Seville, Spain and the John Carter Brown Library.

To give himself a proper framework for his research, he had to learn as much as he could about Mexico, the time period, Spanish texts and the works of other scholars. Only then, Laird said, could he “pay attention to Latin as the elephant in the room.”

“You have to know what the room looks like before you point out the elephant in it,” he added.

Ivy Huang is a university news and science & research editor from New York City Concentrating in English, she has a passion for literature and American history. Outside of writing, she enjoys playing basketball, watching documentaries, and beating her high score on Subway Surfers.